The Falsifiability of Classical Mechanics

Dead As A Doornail

[Thursday, March 20, 2014, (edited a bit today for readability)]

Once upon a time I was enjoying an argument with Smiling Dave on his excellent blog:

http://smilingdavesblog.wordpress.com/2014/02/16/top-ten-economic-blunders-according-to-mises,

The argument wandered around a bit, and eventually, like all the best arguments seem to do, it touched on philosophy, and predictability, and mathematical modelling, and falsifiability so on and so forth.

At some point, Smiling Dave said that if a certain thing happened, then that would disconfirm his understanding of Austrian Economics.

And I said, scenting blood:

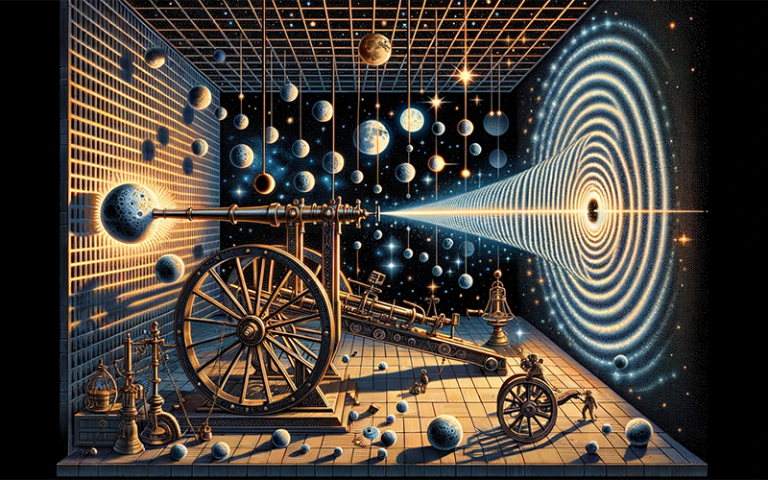

If Jupiter pulls a loop-the-loop, that doesn't disconfirm *my understanding* of physics. That's in flat contradiction with physics, and it means physics is wrong. Similarly with evolution and fossil rabbits in the precambrian.

And Smiling Dave said:

If Jupiter pulls a loop the loop, I doubt the reaction will be to throw out the physics and engineering textbooks. In fact we did have a Jupiter pulling a loop the loop, when quantum effects were first discovered, invalidating all Newton’s laws. So what happened?

And this was a very good question indeed, and it deserved an answer, but my answer is not about Austrian Economics and so I was reluctant to clutter up Dave's blog comments with it, and so I wrote this essay instead:

Classical Mechanics is dead as a theory of how the world works. It survives only as a mathematical model. And we still teach it.

It is still a very useful tool for predicting things. It still makes the predictions that it used to make, and that's good enough for a lot of practical purposes. But anyone who actually thinks that the world works like that is a crackpot and will not be welcome at the sort of parties that mathematicians and physicists like.

Classical Mechanics died before the end of the nineteenth century, from many different directions at once. Once people twigged that the "atoms" idea was actually true, and worked out how electromagnetism worked, and started measuring what happened when tiny fast things crashed into each other, classical mechanics was dead.

People used classical ideas to predict how the atoms would behave, and those predictions were unambiguously wrong. For a time they tried to patch the theory up by adding extra rules, but all those attempts failed miserably.

And so philosophers stopped debating whether classical mechanics was just "true", or whether it was "necessarily true", and they moved on to criticizing mathematicians and physicists for having ever thought it was true, since it is so obviously false.

And I hate to admit it, but the philosophers had a point. If you know a little quantum mechanics, and some more modern ideas about how matter works, you realise that the classical theory was obviously wrong all along, and that if people had only thought a bit harder about it they would have realised that the world couldn't possibly have worked that way.

If I was to go back to 1850 or so, and talk to some clever Victorian physicist, I'd be able to show him that classical mechanics wasn't true with some quite simple arguments and experiments. Nothing that he couldn't have done himself.

Classical Mechanics survives only as a mathematical theory, and in the sense that it is a 'limiting case' of general relativity and quantum mechanics.

But it is still just as useful as it ever was! And remember that that was very useful indeed. Every invention between Newton and the atomic bomb was invented using classical mechanics. Which means that the rise of the West and so the entire history of the world since Newton are squarely the fault of classical mechanics. It is a powerful set of ideas which happen to be untrue.

It can these days be characterized as "A simplified form of general relativity which is appropriate for predicting the behaviour of medium sized slow things, say anything between a ball bearing and a planet, but even then it will be wrong in ways that are not too difficult to spot, once you know what the real answers look like."

Now in fact, very shortly after Classical Mechanics collapsed, dead and greatly lamented by its friends, Einstein and Bohr came up with a couple of new theories about how very small, very large, or very fast things went about their business.

And surprise surprise, those theories turn out to be (a) much better at predicting the behaviour of vsvlvf things, and (b) much less intuitive to human beings, who after all have minds adapted to comprehend the behaviour of the sorts of things humans have to deal with in their daily lives.

Although a conversation with an undergraduate about physics will usually quickly disabuse one of the notion that classical mechanics is intuitive.

Our built-in mental models are much more like Aristotle's version of physics, which is even more wrong than classical mechanics.1

Another surprise is that General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics are also obviously wrong! And in fact unlike the previous theories, they're obviously wrong to us, even though they're also the best descriptions we have of the world.

They are completely different theories, and they can't both be true in the same universe.

And GR makes predictions even more absurd about small things than CM did, and QM is completely incapable of dealing with gravity.

And also QM is famously very strange philosophically, in a way that is hard to explain, but it feels as though it is pulling clever tricks on one at every turn. And the only obvious, straightforward way to interpret the maths is so mind-bogglingly weird that no-one really buys it.2

So although it is our hope that there will one day be a nice big Theory of Everything that can reconcile these two theories, and make predictions about stuff without having to bring in all sorts of ad-hockery and special cases, we sure aren't there yet, and we may never get there.

The smart money says that if we ever find this Theory of Everything, it will be even more weird and its implications even more bizarre than Quantum Mechanics, and that it will include General Relativity as a special case in the same way that Classical Mechanics is a special case of General Relativity.

But if Jupiter actually pulled a loop-the-loop, that would be much much worse.

The orbit of Jupiter is one of the places where Classical Mechanics applies almost exactly. There are tiny corrections from General Relativity, and so in principle you can see that Classical Mechanics is slightly wrong just by looking at the night sky carefully for a while, but nothing that is going to cause loop-the-loops.

And the orbit of Jupiter has been successfully predicted since Newton's time, and is one of the things we know almost for sure about the universe.

If Jupiter pulled a loop-the-loop, then I think our reaction would be utter incredulity.

In fact I think we'd instantly imagine fraud, deception, or incompetence. Even if the data were completely unambiguous and there were millions of witnesses and no possible way it was a trick, I think we'd end up treating the event in the same way we treat the Miracle of Fatima, as a massive delusion simultaneously and inexplicably affecting vast numbers of otherwise intelligent and reliable minds.

And I think we'd be right to. Unlikely as that is, it's way more likely than Classical Mechanics being so completely wrong about something that is so unambiguously in its approximate domain.

But if Jupiter repeatedly and unambiguously started pulling loop-the-loops, what then?

Well, two options:

(a) Someone comes up with a new theory that cleverly and elegantly explains what is happening, and also explains all the previous data as well, including the near-total success of CM on planetary orbits to date, which I reckon is a “highly non-trivial”3 thing to do.

(b) We give up. We figure that even though we've got all these clever physics theories and they explain so much so well, we just can't trust that way of thinking. We go back to believing that the universe has a mind of its own, and that angels push the planets around, or that we're living in a giant computer game, or some such wooo.

We'll still use our theories, because they're so useful, but they're just 'rules of thumb' for working out 'how angels like to move planets'. And science as a philosophy is dead. We live in a magic world.

Aristotle's physics is not so wrong that it was obvious to people before Galileo that it was wrong. It's actually pretty good if you want to describe everyday happenings in the world of the ancients. Again, there are some nitpicks, and I could easily convince Aristotle that his physics was wrong, but only because I know more about what really goes on, and so I know where to look for the strange behaviours that his theory doesn't account for.

True when I wrote this, but these days more and more people are coming to accept that the straightforward everything everywhere all at once magic reality fluid view is the right way to look at things.

Maths slang for the difficulty of problems such as P vs NP, or the Riemann Hypothesis

I love it. But when you originally took issue with Smiling Dave's characterization of the pickle he'd be in if certain things happened that forced him to question Austrian Economics, you specifically zeroed in on the "my understanding" part. Would Smiling Dave have to revise his understanding of the theory, or abandon it when confronted with evidence that it's wrong? I thought the essay that flowed from that would be about or at least touch upon the distinction between theories and the realities they attempt to describe. But you answered his question of "what happened" with an account of how theories of physics have been shown to be wrong but have not been abandoned due to their practical utility, as opposed to their failure in providing correct and complete descriptions of reality. Hmm. Now that I write that, maybe that actually does touch upon what I thought it would.

So you actually seem to be agreeing with Smiling Dave, then, with the caveat that we ought not think about our theories and what they describe interchangeably.

And if the theories are wrong or incomplete (is there a difference?) it follows that we live in a magical world? I would need more convincing to agree. It seems that although we don't have a theory that provides a satisfactory model, we can't foreclose on the possibility of one existing. Even if we currently see no avenue to discovering it, I don't think we have to despair and conclude the universe has a mind of its own or angels are pushing planets around or it's turtles all the way down or anything like that.